Strings

All About Guzheng Strings

Jump to: Type | Nylon | Drawn Wire | Silk | SRope Core | Additional Materials | String Gauges | String Lifespan | String Care

Strings control a guzheng’s timbre. Modern instruments are usually strung with "Nylon" strings which are actually a core of drawn steel, a winding of copper (for bass strings), a tight thread layer, and then a final nylon winding. The ends are wound in an additional layer of thread and shaped for the anchors. Other materials have been used throughout the ages. Read on to learn about different materials, string gauges if you need to replace them, and how to take care of your instrument’s strings.

Type A, Type B, etc

You’ll often find mention of Type A or Type B strings. These are standards put forth by the Dunhuang Brand. There are 4:

Type A

The first standardized nylon wrapped, steel-core strings, produced in 1975 by the Dunhuang company. First simply named “Dunhuang strings”, these are designed with a lower tension than later revisions. Lower tensions allows more subtlety and finesse in the embellishments and pitch bends that the traditional guzheng is famous for. As of 2021, Type A are still produced and some instruments are made for Type A strings. Strings are typically white with the “A” notes colored. Dunhuang colors with green, Zhuque colors with red.

Type B

The second standard released in 1997. Type B are designed for higher tensions which 1) changes the timbre of the sound to fit evolving preferences and 2) makes faster playing styles “easier”. That is, the strings respond to faster movements differently in a way that helps performers. As of 2021, Type B are the most common strings out there. Strings are typically white with “A” notes colored. Dunhuang colors with green, Zhuque colors with red.

Type C

The third standard, released in 2005. These are both a classification and a set of strings - the complete set needed to tune a guzheng with 8 notes per octave instead of the traditional 5 notes. This was done to help adapt the guzheng to western pieces and to ease its inclusion among western orchestral instruments. Type C strings are easily distinguished by their 3-color pattern: Green for A notes, Red for D notes, and white for everything else.

Type D

Dunhuang multitonic guzheng model 697-1 taken from guzhengw.cn

The fourth standard released in ~2011 (still looking for a definite date). This is a special set designed for a particular subclass of guzheng, the Multi tonic guzheng, 多聲弦制箏 (Duō shēng xián zhì zhēng). This guzheng doubles up on strings: There are 16+ super short pentatonic strings, 15+ short diatonic strings, and about 6 normal length diatonic strings.

The picture shown here is a Dunhuang model 697-1 with 37 total strings. By about 2017 Dunhuang released the 697-3, a 45-string model (20 pentatonic, 25 diatonic).

Materials

Nylon wrapped, steel core

Nylon strings are the most common because it is:

Relatively cheap to make

Can be made of consistent quality

Durable, last longer

Is more comfortable to play

Has a well-rounded sound

Can be held at a higher tension, producing a louder sound and allowing for faster play styles.

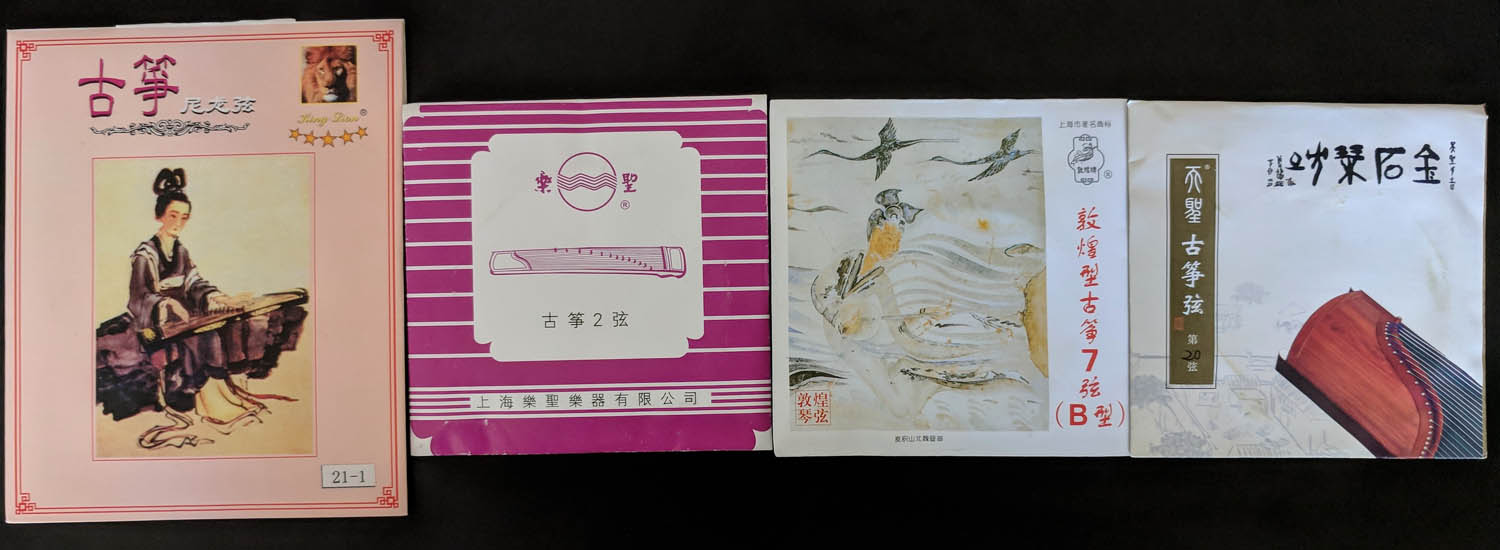

Reputable string manufacturers/brands include: Alice, Daishi, Dunhuang, Tiansheng, Xianjing, Yuesheng, and Zhuque.

Compare that with the other materials:

Drawn Wire

Update Aug 2020: Sound of China is now carrying steel strings!

Effectively the core of the modern string, drawn wire strings were made of steel, steel wound in copper, straight copper, or brass. Metal strings are more durable than silk, easier to produce consistently, and louder. Their timbre is described as bright, emphasizing higher frequencies. Too much high frequency can be unpleasant to the listener. Wire strings transmit the nuance of left-handed techniques better than nylon but not as well as silk. Left-hand ornamentations can be painful to play on higher-tension and thinner wire strings.

Accordingly tensions are generally lower, preventing the instrument from being used for modern, faster techniques. Sources: Cheng 1991, Han 2013

Silk

Silk was considered one of the best materials for strings for a very long time. It transmits nuances that metal and nylon strings simply do not capture. However:

Silk strings are expensive and prone to breaking. They are quieter and require frequent tuning. They are kept at a lower tension in order to emphasize fine nuances, prohibiting modern, fast techniques. Silk strings are said to have a 'dull' tone that does not transmit higher frequencies as well as metal strings. Sources: Cheng 1991, Han 2013

There is a strong sense of culture and history thanks to China's connection to silk but it is rarely used today.

Nylon wrapped, “rope” core

Update Aug 2020: Alice string company has released a Silk-sounding nylon string set and Sound of China has started selling them!

These are purported to be a compromise between the sound of silk strings with the durability of nylon-wrapped stings. I have not seen them or heard them played but they are on my list to try!

Catgut and Animal Hair

While rarely discussed in modern English sources, strings were made from whatever materials people had on hand. The guzheng manufacturer Tianyi published an overview referencing animal hair and animal "tendon" being used as strings:

历史上的古筝弦经历过几个阶段,较早是一般使用动物的筋风干为弦(鹿筋),也有以动物的毛发为弦(马尾),这类弦的优点是声音柔和,缺点是音量小,易走音,使用寿命短.

The zither string has gone through several stages in its history. Early on strings were made of dried deer tendon [species: Cervus elaphus] or hair from the deer's tail. The advantage of these types of strings is their soft, pleasant sound. The disadvantage is their small volume, (易走音?), and their [short] service life.

Carole Pegg writes in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians that the Mongolian zither the yatga is said to have had strings made from a variety of materials including horse hair and animal intestine (also known as catgut). It is perfectly possible that Chinese zithers were strung with such materials at some point and place in time.

String Gauges

One common question is what thickness of string is appropriate for which location on the instrument. This is especially important when people are trying to replace a broken string on an older guzheng with drawn wires. There is no universal standard as to what thickness of string should be used at which point on an instrument, but there are some general trends observable on modern instruments. Below are the thicknesses of strings on 8 different guzheng, ranging from steel to wound copper to nylon. Guzheng A-D are 21-string guzheng with modern nylon strings. The first two are full size, the last two are travel size.The remaining Guzheng E-H are drawn-wire guzheng, strung with steel or copper-wound steel.

Notes:

All measurements were taken in inches. The second chart has the same measurements converted to millimeters.

The 16-string guzheng used far thinner wires than the 18-string.

The sudden jumps in thickness around strings 14+ are from the addition of copper windings.

Wire is sold by its "gauge" but there are several competing measurement systems. Use this link to convert from diameter to gauge.

Guzheng String Diameters, Inches

Guzheng String Diameters, Millimeters

String Lifespan

Modern strings last for different lengths of time depending on how much they are played, the tension used, and how energetically they are struck. The brand Tianyi suggests in their knowledge base that strings will last for 2 years if played daily for one hour. Carol Chang suggests that the thinner, higher-pitched strings last 6-12 months while the thicker bass strings can last more than 2 years.

The real deciding factor is your preference for the sound. Over time the string materials wear out. The timbre of their sound changes. You'll be able to get them to a desired pitch, but the extra qualities that make guzheng music so special will alter. If the sound doesn't bother you there is no need to change strings. I know guzheng players and teachers who only change strings when they break.

String Breaking and Care

Let's get a fear out of the way: yes strings can break but they are unlikely to hurt the player or the instrument. The metal wire in the center of a string is what fails first. When it fails all of the string’s tension is passed to the nylon winding which will stretch suddenly. It may startle you but it won't hurt you.

Tension and striking force are what wear strings out. High tensions wear strings out faster. Poor tuning practices are another prime culprit. If, when tuning, you change the pitch of the strings drastically without lifting the strings off the bridges, the tension cannot equalize across the string. It concentrates at the movable bridge and can snap. Some, especially the treble strings, are easy to break when tuning.

To avoid these issues, follow the guidelines for tuning and check the charts for bridge placement for each key. If your bridges are close to those locations and you are using the correct string for each space on the guzheng, your strings won't be too tight. If your bridges are way far to the left, towards the tail, that's a sign your tensions are too high.

The last thing to consider is that every brand and quality level of string is different. Each set can have a different timbre and last a different length of time. The lifespans given above are benchmarks. Your mileage may vary. If multiple strings break while playing and it's been a while since you last bought new strings, consider getting some replacements. If the strings are new, it's a sign the instrument is at too high of a tension or is being mishandled in some way.

Common Breaks:

Player’s area: the string just wore out.

On a fixed bridge: the tension was too high for the string. Maybe it was a flawed string, maybe the string snagged on the fixed bridge, or maybe the movable bridge is too far to the left.

On a movable bridge: High tension, likely caused by poor tuning habits.